Cathy Berberian was born Catherine Anahid Berberian on July 4, 1925 in Attleboro, Massachusetts to Armenian parents. She was the elder of two children to Yervant and Louise Berberian. The family moved to New York in 1927 and lived in New Rochelle before settling in the Bronx where Cathy would attend Catholic grammar school.

From an early age she took an interest in traditional Armenian music and dance, and demonstrated a proclivity for popular song and the dramatic arts, often performing with her father to entertain family and friends. It was ultimately her mother’s record collection that led Cathy down “the long rabbit hole into the wonderland of music” when she was seven years old. One particular recording cast such a deep impression on her that she secretly vowed her life to singing: it was Tito Schipa singing “Ecco ridente in cielo”, from Rossini’s The Barber of Seville.

Cathy’s early aspirations were operatic, and she admired French-born American coloratura soprano Lily Pons as well as Fyodor Chaliapin, the Russian bass famed for his operatic stage presence. Prefiguring the exceptional three-and-a-half octave range for which Berberian would later be known, young Cathy liked to sing with Pons’s recording of the “Bell Song” from Delibes’ Lakmé (notorious for its high F) as well as Chaliapin’s recording of Mussorgsky’s bass showpiece, “The Song of the Flea.”

Her family moved to the Woodside area of Queens around 1937, and Cathy attended the elite Julia Richman High School for girls in Manhattan’s Upper East Side where she excelled in literature and writing. She took voice lessons through high school singing in an amateur chorus during high school, and she was actively involved as a soloist and director for the Armenian Folk Group of New York. Upon graduation, she enrolled as an undergraduate at New York University. Though her parents had reservations about a singing career, Cathy believed otherwise and soon left the university to focus her studies elsewhere. She worked during the day to support night classes in theatre and music.

At Columbia University she studied under Milton Smith, director of the Brander Matthews Theater, Herbert Graf, instructor of the Columbia Opera Workshop and a theatre director at the Metropolitan Opera, and silent screen and stage actress Getrude Keller. Cathy took courses in opera, voice and diction, stagecraft, pantomime, and radio writing. On other nights she went to La Meri’s Ethnologic Dance Center and studied Spanish and Hindu folk dancing to master the requisites to one day play the roles of Carmen and Lakmé.

Berberian’s parents consented to their daughter’s vocal pursuits in 1948 by supporting a short-term study in Paris with Marya Freund. In 1949, Cathy journeyed again abroad, this time to the Conservatorio di Musica Giuseppe Verdi in Milan and received vocal training from Giorgina del Vigo. Her studies with Del Vigo were a turning point, for under her tutelage Berberian retrained her voice as a mezzo-soprano and discovered a vast repertoire of chamber music that highlighted the multi-faceted qualities and texture of her voice. Del Vigo also instilled in her the importance of interpreting the music beyond technique through performance instict. Cathy made plans to apply for a Fulbright Fellowship in order to continue her studies in Milan, and while looking for a pianist to play at her audition was introduced to Luciano Berio (1925-2003), at that time a composition student and vocal accompanist at the Conservatorio. According to Berberian, “He spoke no English and I spoke no Italian. We had no contact but music.”

Though Luciano was unable to accompany Cathy on the recording, by spring 1950 he proposed marriage and she received the Fulbright award. They married on October 1, 1950 and settled in Milan, where Berberian would make her permanent home, and on November 1, 1953 they welcomed a daughter, Cristina Luisa. The start of their personal and professional union was auspicious, and the collaborative relationship that burgeoned over the decades enabled some of their most significant achievements.

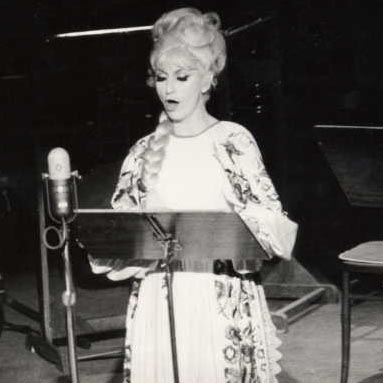

Cathy appeared in a number of concerts during the early 1950s, including a small production organized with Berio at a theatre just outside of Milan in which she played Alisa in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. Her formal début came in Naples on June 17, 1958 for the closing concert of Incontri Musicali, a new music series inaugurated by Berio and Bruno Maderna the prior year in Milan. She performed Stravinsky’s Pribaoutki and Ravel’s Trois poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé. Success in Naples was followed by a critically acclaimed performance on January 5, 1959 at the Accademia Filarmonica in Rome, where Cathy gave the première of John Cage’s Aria, sung simultaneously with the electroacoustic work Fontana Mix. The Fontana Mix had been Cage’s sole project during his residency at Berio’s Studio di Fonologia in winter 1958, but Aria was the inspired outgrowth of hearing Berberian’s mimicry and unique vocalisms during her work on Berio’s Thema (Omaggio a Joyce). Cathy Berberian’s reputation as a recitalist of new music was firmly established after her performances at the Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik in Darmstadt, Germany in September 1959, and she quickly became the muse to numerous composers who wrote new works expressly for her, including Bruno Maderna (Dimensioni II: Invenzione su una voce, 1960), Roman Haubenstock-Ramati (Credentials or Think, Think Lucky, 1961), Igor Stravinsky (Elegy for J.F.K., 1964), Darius Milhaud (Adieu, 1964), Sylvano Bussotti (La Passion selon Sade, 1965), Henri Pousseur (Phonèmes pour Cathy, 1966), and William Walton (Façade 2, 1977), among others.

Moreover, though her marriage to Berio ended in 1964, their professional relationship flourished during the 1960s, marked by a succession of groundbreaking works for voice that remain essential to the vocal repertoire today: Circles (1960) for voice, harp, and percussion, with which Berberian made her United States début on August 1, 1960 at the Berkshire Music Festival at Tanglewood, Epifanie (1959-61; rev. 1965) for voice and orchestra, the electroacoustic work Visage (1961) created from Cathy’s vocal improvisations, Folk Songs (1964) arranged for voice and chamber ensemble, and Sequenza III (1965-66) for solo voice.

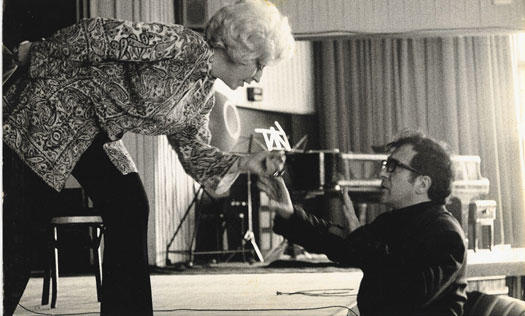

Cathy gained notoriety as a virtuosic interpreter of new music and was esteemed for the extraordinary wit and intelligence with which she approached any project. She possessed an astonishing “rapid-reflex” technique by which she shifted seamlessly between disparate music styles, invoking Marlene Dietrich, baby talk, bird call, and Sprechstimme in one musical line, and her impeccable vocal technique also lent insight to stylized trilling and ululation.

Cathy viewed the voice as an unlimited instrument and was constantly exploring its possibilities. The theatrical element was always present in her performances. Her stage presence was striking and unforgettable, due to her personal charisma, her wit, and her remarkable ability to capture the mood of a work through physical gesture, lighting, costumes, and even stage props. She was a master at communicating instantly with her audience, even the most musically conservative and hostile. While Berberian was a devout exponent of contemporary music, performing new compositions at concerts and festivals throughout the world, she gave nuanced interpretations to familiar works by Monteverdi (whose music she rediscovered in the late 1960s), Purcell, Stravinksy, and Debussy, and included regularly in her recital programs music by Weill, Gershwin, The Beatles, or salon and cabaret songs as well as traditional folk songs.

In 1966 Berberian composed her first musical work, Stripsody for solo voice, an exploration of the onomatopoeic sounds of comic strips, which she used to convey a succession of amusing vignettes, illustrated by Roberto Zamarin. In 1960, she had translated into Italian Patricia Hutchins’s James Joyce’s World with Roberto Sanesi, stimulated by the exploration of onomatopoeia in Berio’s Thema. Then with Umberto Eco in 1962, out of her longstanding love of comic strips, she undertook an Italian translation of the American political cartoons by Jules Feiffer.

She composed a second work in 1969, a piano composition entitled Morsicat(h)y, also illustrated by Zamarin. In later decades Berberian was actively involved in concert, recordings, and masterclass engagements, including an invitation in 1972 by stage director Peter Brook to the International Centre of Theatre Research in Paris to lead a three-week workshop on acting and improvisation.

Cathy Berberian died at age 57 on March 6, 1983 after suffering a massive heart attack in Rome. She was due to appear the following day on Italian television in a performance to commemorate the centennial death of Karl Marx. She had planned to sing a rendition of the Communist Party anthem “Internationale” in a ‘Marilyn Monroe’ style.

In the last 4 years of her life, Berberian had also been struggling with a hereditary eye condition which crucially impaired her vision, forcing her to memorize every score she had to perform.

As a testament to the vacuum she left in the musical world, Berio utilized multiple singers to satisfy the single role Berberian had once filled in the performance of Folk Songs at a 1994 memorial concert at La Scala. Berberian was the most celebrated vocal recitalist of her time. Her contributions to postwar music are amply and unequivocally evident, and the historical impact of her artistic achievements continues to be highly appraised.

As a testament to the vacuum she left in the musical world, Berio utilized multiple singers to satisfy the single role Berberian had once filled in the performance of Folk Songs at a 1994 memorial concert at La Scala. Berberian was the most celebrated vocal recitalist of her time. Her contributions to postwar music are amply and unequivocally evident, and the historical impact of her artistic achievements continues to be highly appraised.

(courtesy of Rebecca Y. Kim)